Elevating the deal discussion

With few exceptions, companies depend on growth for survival and success. That can happen naturally through expanding the customer base or introducing new products and services. But getting ahead often means inorganic growth – that which comes through other actions, usually deliberate and sometimes dramatic. This may be a response to disruption or a proactive step to advance a company’s strategy. Whatever the reason, choosing the right mechanism for growth is crucial.

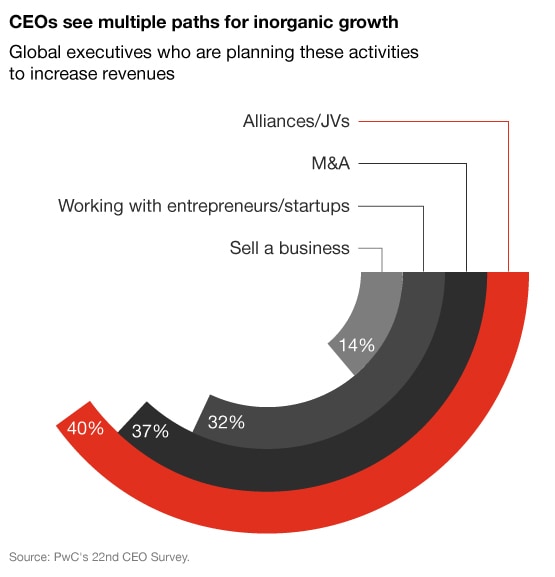

Among the most common paths for inorganic growth are mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and strategic partnerships, such as alliances and joint ventures (JVs). These types of deals have become more important as industries continue to evolve and the lines between some of them blur. Such shifts can make previous paths for organic growth obsolete. Consider the entertainment industry and how movies are watched now compared with 10, 25 or 50 years ago. Or the US airline industry, which now has only a dozen large carriers, with four controlling about 80% of the market. Faced with different types of disruptions – technological, demographic, geopolitical – companies must keep their growth options open.

Similar goals, different advantages

Acquisitions and alliances can achieve similar goals. Both allow a company to expand its reach – through access to new products or services, new geographic or industry markets, or new types of customers. Both can open the door to additional or new resources, such as technology and talent. Both typically require a significant investment of financial capital, time commitment and executive oversight.

While both deal types can drive business growth, deciding whether to buy or partner with another company can be daunting. Each brings its own challenges along with the benefits, and choosing wrong can leave a business chasing competition, mired in financial straits or struggling in other ways. CEOs, company owners and other leaders can’t afford those missteps.

That’s why it’s essential for businesses pursuing growth to understand the key considerations in determining if an acquisition or an alliance is the best path for inorganic growth. These include important questions and distinctions about capabilities, control, cost and conditions beyond a company’s control. Companies also need to recognize the role of divestitures in their growth decisions, as well as situations in which M&A and partnerships both could make sense.

When deciding on an acquisition or alliance

- Capabilities: Filling a gap or building on strengths

- Control: Weighing investment, access and ownership

- Cost: Determining the business ROI

- Conditions beyond control: Predicting success based on external factors

- Keeping the right pieces: The role of divestitures

- Best of both worlds: When a partnership + M&A makes sense

Capabilities: Filling a gap or building on strengths

Many deals are made to improve a company’s capabilities or its portfolio of products and/or services.

Enhancement can be one goal – filling a capabilities gap or responding to a change in the market.

- An acquisition could open up all of a target company’s capabilities – including some the acquirer may not want – and be the only way to access core capabilities. An acquisition also allows longer-term access and the ability to integrate and maintain capabilities. That could improve the potential for more value from the deal.

- With a partnership, a company can pursue new capabilities to benefit specific parts of the existing operations or portfolio. An example is gaining access to a new region or market that may be narrow enough that the company doesn’t want to integrate the entire target. Another scenario is a company’s inability to handle an integration but desire to maintain an ongoing relationship.

Or a company may want to leverage existing capabilities – building on strengths with another company’s products and services.

- M&A makes sense if all or most of the target’s products and services can benefit from the acquirer’s capabilities. Those that don’t fit could be candidates for divestiture.

- An alliance may be preferable if the target’s products and services don’t provide independent value when combined with the acquirer’s capabilities system. In this situation, the target’s products and services could be bundled with the acquirer’s products and services.

Control: Weighing investment, access and ownership

When developing an inorganic growth strategy, companies should be ready to determine the importance of ownership vs. partnership with each deal. The former provides control but typically requires more commitment. The latter allows more flexibility and can reduce risk but may limit use of the desired assets.

A potential acquirer needs to assess if owning the assets is the only way to achieve maximum value or if they can be accessed without equity. This means asking if the assets are unique and central to the growth strategy or if comparable market alternatives are available. It also includes determining if full control is needed to align the people, assets and systems or if a legal agreement can accomplish the same thing while keeping the parties independent.

Situations in which full control through M&A could make sense:

- Opportunities that involve more specific, durable assets, due to longer time horizons and larger capital outlays.

- Deals involving highly complex products or proprietary products and services.

When a lesser commitment via an alliance or JV may be preferable:

- When companies need access to a capability but can’t or don’t want to maintain it themselves – if building the capability might be expensive or too far outside their business strategy, for example.

- When the target is a market leader or has a strong reputation, which can elevate the price of an acquisition, leaving a partnership as a more manageable way to gain access.

Cost: Determining the business ROI

Acquisitions and alliances both require investment. When trying to decide which deal makes more sense, a company needs to determine the value related to cost for each option.

An acquisition often costs more than a partnership, and a big question is if the premium is worth it in the end. A company should evaluate the post-deal value of each option to determine whether the cost of full control exceeds the cost of collaboration – both establishing and maintaining an alliance or JV.

In an acquisition, value is often created through synergies in costs and revenues.

- Integrating operations, product or service delivery, support systems and other functions can be difficult but ultimately should create efficiencies that improve the bottom line.

- As long as these synergies outweigh factors that destroy value – such as ownership premiums caused by the acquisition or areas where synergies aren’t available – an acquisition should produce value.

A partnership can create value without a company assuming some of the above risks.

- Each company may be able to leverage the other’s capabilities as separate entities, while integration or other changes to operations or systems would require significant financial commitment.

- Even if the investment isn’t evenly split in a partnership, combining assets or resources can result in new synergies each partner wouldn’t have had otherwise, unlocking more value.

Conditions beyond control: Predicting success based on external factors

Beyond specific deal details, factors outside a company can influence whether an acquisition or alliance would deliver more benefits.

Consider the number and willingness of potential partners. A company should assess all potential targets/partners in the market and gauge the value of either M&A or a partnership with each. Even if there was previous dialogue and a proposed deal structure with another company, further investigation could reveal a better fit.

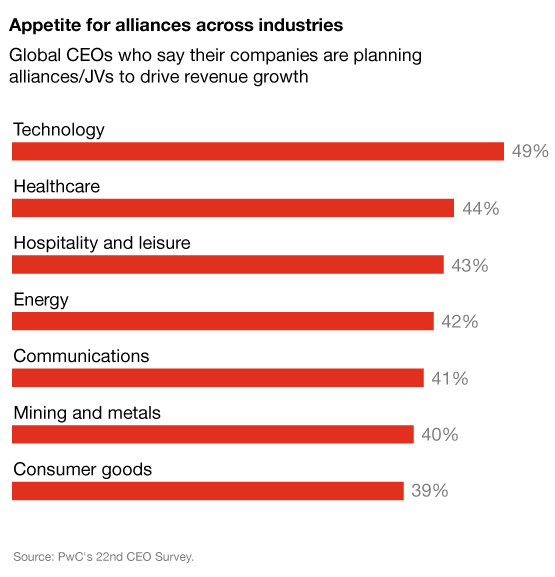

Market and other dynamics also require scrutiny before deciding on the type of deal. Certain industries may be predisposed to acquisitions, while others may have been more favorable for partnerships. A company should assess how hard generating meaningful value would be if it takes the less-traveled path.

Some industries may face pressures that affect a deal decision. For instance, activist shareholders could be pushing companies to focus on core capabilities and avoid diversification, limiting the appetite for acquisitions. Companies also should consider not only their stakeholders but how competitors may react to an acquisition or alliance. The expected benefits could be offset by a rival striking its own deal.

The life cycle of a product or technology could increase risks and move the decision toward a partnership. And deals that cross industry or country lines can pose hazards, especially for inexperienced companies. A company needs to look beyond business considerations to political risks and other factors that could influence the acquisition/alliance decision.

Keeping the right pieces: The role of divestitures

An increasingly important part of a company’s growth is ensuring that it follows the overall business strategy. A historically active acquirer may find some businesses and operations – even if well-performing – no longer mesh with its current direction. The same can apply to a new acquisition, in which selling an unnecessary part can unlock more value.

If a business isn’t essential, divesting can provide capital for a deal that helps execute the growth strategy. Increasing the money dedicated to company strengths can boost the prospects of creating more value.

A divestiture also doesn’t have to be a full sale or spin-off. It can be part of a JV that keeps the company involved while providing access to new assets. If a business is underperforming, a divestiture into a JV – perhaps with an experienced private equity firm – can allow for a turnaround that eventually brings value.

Best of both worlds: When a partnership + M&A makes sense

Just as a company doesn’t have to rely solely on acquisitions or alliances in its growth strategy, it may not have to choose one over the other with certain opportunities.

A company could be interested in acquiring a business but not yet willing or able to pursue the transaction. A partnership with an option to buy can open the door without the would-be acquirer overextending itself. It also gives both companies flexibility – in particular if the relationship doesn’t perform as expected and an acquisition no longer makes sense.

Or a company may be ready for an acquisition, only to find targets aren’t available. A successful strategy should determine the best course for growth, not look at what’s for sale and try to make something fit. A short-term partnership can provide experience in a particular area while an acquirer waits for its preferred target. And the partnership could be successful enough that the parties explore M&A.

Next steps

When organic growth isn’t enough, companies need to decide which deals will generate value and move their businesses forward. An effective growth strategy recognizes that M&A and partnerships both can drive expansion. Determining which transaction is best for certain situations is critical for an optimal return on investment.

C-suite executives, corporate development teams and other dealmakers can navigate the question of acquisition or alliance by gaining more insight on key considerations for inorganic growth. Capabilities, control, cost and conditions beyond a company’s control all play important roles in deciding on the deal type.

Organizations that don’t have a firm grasp on these aspects of a deal should seek that expertise and incorporate it into their inorganic growth discussions. By improving their understanding of the advantages and challenges of M&A and partnerships, companies can make better decisions on deals that deliver higher value.