How better negotiations of post-closing price adjustments can protect and enhance deal value

05 February, 2021

In any economic cycle, most M&A transactions in the US involve some form of a post-closing price adjustment. With dealmakers navigating increased economic uncertainty, buyers and sellers are at even greater risk of a disconnect in pricing positions and interpretations of deal terms. Failing to prepare for those negotiations and potential disputes could result in substantial loss of deal value.

Post-closing disputes can be lengthy, expensive and distracting, and they inevitably create uncertainty over the final purchase price. Whether you’ve recently completed a deal or are in the middle of a challenging post-closing price negotiation, you have options to protect and even enhance your deal value. The closing statement and the counterparty’s dispute notice are each side’s only chance to put their pricing position on the table, so they should do so thoughtfully.

What’s the typical post-closing process?

Before examining options, let’s look at the components of price adjustments in a closing accounts pricing mechanism and how the process ultimately affects purchase price. A typical closing statement sets out the balances required to calculate the final purchase price — usually some combination of cash, indebtedness, working capital and seller transaction expenses.

- A closing statement is prepared in accordance with the terms of the agreement, which has been commercially agreed by the parties.

- A closing statement is not a GAAP-based audited statement, the buyer’s opening balance sheet or the purchase price allocation.

Unless otherwise commercially agreed to, the closing statement has a dollar-for-dollar impact on the purchase price, and buyers and sellers must dedicate time and effort to prepare and review this pricing statement or risk leaving significant value on the table.

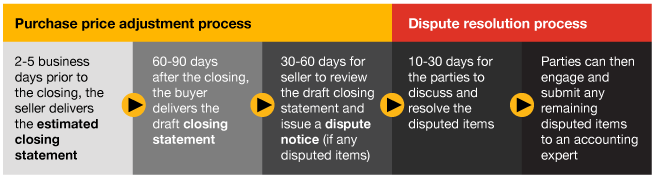

After legal closing, a purchase price true-up occurs calculated as the difference between (1) the estimated closing statement (i.e. estimated cash, indebtedness, working capital and seller transaction expenses), which is prepared by the seller prior to closing, and (2) the final closing statement (and each component thereof), which is measured as of the closing date but typically prepared by the buyer 60 to 90 days after closing.

Tips for navigating post-closing price adjustments

Potential issues surrounding post-closing price adjustments are exacerbated during times of uncertainty, including the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic. So preparation and strategy become even more crucial.

1. Preparation is key

The practical requirements of the closing statement process, such as meeting the submission deadline and having the right resources, can be as important as the commercial and contractual considerations relating to agreement interpretation and application of judgment. They present logistical challenges that, if not addressed, can erode deal value.

For an optimal outcome, a dedicated decision-maker with a broad understanding of the commercial negotiations that took place pre-signing should oversee the post-closing price adjustment process. Parties are now navigating difficulties of working virtually in addition to existing deal complexities, while still having to meet the condensed time frames established in the sale and purchase agreement. This makes it even more critical to have focus and accountability in the process.

For the preparer, once the position is set in the draft closing statement, dealmakers will not have another opportunity to make (favorable) adjustments. The preparation time is the only time you have to solidify your position to extract or protect value.

Key tips

- Make sure you understand the key terms and basis of preparation set out in the agreement and how those translate to the accounting at closing.

- Agree on your understanding of the accounting principles and/or “GAAP consistently applied.” Consider whether consistency or GAAP will take priority, and how you can defend your preferred pricing position.

- There is typically no concept of materiality in application of the deal accounting principles and no substitution for doing a thorough, detailed review of at-risk accounts.

- Understand the key areas of judgment or interpretation and work with your deal advisory team to understand the strongest arguments to support your position.

- Have a candid conversation with key stakeholders about your strategy, balancing commercial considerations with the reality that you have only one opportunity to propose favorable adjustments.

For the reviewer, the dispute notice must have all known areas of disagreement included, as common practice nearly always includes clauses prohibiting introduction of new deal issues.

Key tips

- Have a strategy from the outset to avoid giving away deal value too early in negotiations.

- Anticipate your position on all potential areas of disagreement and prepare rebuttals.

- Understand what access rights you have negotiated and prepare a detailed information request list to make on Day One.

- Make sure to verify that any liabilities are not double-counted — either within indemnification or the closing balance sheet.

- Don’t simply dispute adjustments made by the preparer, but take the added step to identify proactive adjustments based on the agreement terms.

- Circulate a template of the dispute notice to your team and start to populate with areas of focus from the diligence process and any areas of judgement.

Case in point #1: The consequences of not being prepared

- Relying heavily on the seller’s pre-closing estimates and not performing a financial close of the books and records, the buyer prepared a mid-month closing statement resulting in a post-closing price adjustment of $15 million to be paid to the buyer based on the following period-end financials.

- The seller delivered a dispute notice targeting certain subjective areas, including the refinement of its pre-closing estimates and putting forward a seller-favorable post-closing price adjustment of $25 million, leading to a $40 million spread between the parties’ positions.

- During the good faith negotiations, the buyer performed a financial close as of the mid-month closing and identified an additional $5 million of downward adjustments on disputed and undisputed items.

However, the contractual resolution process did not allow for the introduction of new items at this stage. Therefore, the buyer couldn’t avail themselves of the favorable adjustments identified during the late mid-month closing process and couldn’t use the $5 million in deal value to offset the unfavorable adjustments proposed by the seller.

2. Be strategic from the start

Regardless of your role in a transaction, knowing all possible pricing levers in an agreement will help you develop a holistic position and negotiate the best value for you and your stakeholders. Those levers include the closing statement, representations and warranties, indemnities, side arrangements, intercompany settlements and terms of transition service agreements (TSAs).

The post-closing price adjustment process is one of the final steps in a deal. Although there is a prescribed timeline in the agreement, parties sometimes engage in prolonged discussions well after the closing date. Strategically laying the groundwork for the twists and turns of the negotiations to a final purchase price will help avoid giving away value too early in the process.

Business pressure caused by the economic recession and changing political and regulatory environment will likely impact both the negotiation strategy and the timeline. Though you may not be able to predict everything that could happen, modeling potential scenarios and outcomes will allow you to be more effective during these negotiations.

Key tips

- Understand the rules at play and avoid creating boundaries that do not contractually exist.

- Focus on negotiation strategy to finalize purchase price, rather than “getting it right” for the opening balance sheet.

- Remember that the closing statement calculations are based on the contract terms, which are not always strictly in accordance with GAAP.

- Appreciate that the purchase price adjustment is not simply a roll-forward of financial diligence, and the purpose differs from that of an opening balance sheet or purchase price allocation exercise.

- Consider the strength of your arguments in judgmental areas, weighted with the age-old adage: If you don’t ask for it, you won’t get it. Both parties may be incorporating items with stronger and weaker arguments, respectively, and each will be subject to good faith resolution.

- And while the agreement may be prescriptive for the accounting expert’s determination, parties can still bring matters to the table before the expert’s involvement under a “good faith” argument. (For example, upon delivery of the closing statement, the buyer identifies a computational error and requests the seller consider an amended closing statement in good faith).

Case in point #2: Being strategic from the onset will benefit future negotiations

- Management prepared preliminary financial statements as of closing showing an incremental purchase price due to the seller of approximately $30 million.

- The seller was responsible for preparing the closing statement and identified significant positive and negative adjustments to management’s preliminary financial statements. The result was a net downward adjustment of $20 million as compared to management’s financial statements, with the net purchase price increase due to the seller only $10 million.

- The buyer and seller had an ongoing commercial relationship, and the seller was incentivized to finalize the post-closing price adjustment process quickly for commercial reasons. The seller initially wanted to issue the closing statement inclusive of all the identified adjustments, both favorable and unfavorable (i.e., resulting in a $10 million payment to the seller).

- After strategic discussions, the seller ultimately held back many of the unfavorable adjustments identified and put forward a closing statement with mostly favorable adjustments showing a payment due to the seller in excess of the expected $10 million. This allowed the seller to create a buffer to protect its pricing position; however, the seller was willing to negotiate to the $10 million point.

- The buyer responded with an unexpectedly aggressive dispute notice with a $31 million downward post-closing price adjustment but in doing so failed to identify $3 million of the downward adjustments that had been held back by the seller.

The strategy put in place before producing the closing statement allowed the seller to negotiate more leniently on the amounts proposed by the buyer without leaking value, which quickly resolved the negotiations.

3. Know the potential pressure points

The issues that were most contentious during the pre-signing process will likely become equally contentious – and subject to dispute – after closing. This is likely to be magnified in times of uncertainty, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prepare yourself with the best arguments that support your preferred pricing position and with rebuttals for positions that may be presented by the other side.

As a seller, it helps to gather relevant historical accounting information and records before closing. After that point, the books and records will likely be controlled by the buyer, and access, even if contractually allowed, will inevitably be limited and possibly restricted.

As a buyer coming to grips with a newly acquired business, ensuring you have full access to all the target company’s historical information and relevant facts will better guide the formulation of the closing statement.

In challenging economic times, it is more likely that a buyer may try to take aggressive positions in the closing accounts. For example, a buyer may attempt to record more conservative inventory reserves at closing if there is a precipitous drop in sales post-closing. This makes it even more critical that sellers focus on access to historical records before transferring the business to ensure they can demonstrate consistency with the contractually required accounting policies.

Having an initial kickoff or strategy meeting to discuss known issues before the post-closing preparation or review clock starts ticking helps make sure all teams – finance, accounting, legal, tax and external advisers – are aligned, as time will be of the essence.

It helps to remember that disputes often relate to areas of accounting judgment around accruals, reserves, provisions and the point of recognition of a particular asset or liability.

Case in point #3: The same pressure points persist

- During diligence, significant inventory buildup was identified in excess of what appeared reasonable given projected sales growth. Instead of addressing inventory directly in the sale and purchase agreement, the buyer assumed they would be able to address it in the closing statements.

- The sale and purchase agreement required the closing statement to be drawn up in accordance with GAAP consistently applied. Historically, no provision was included for excess inventory in the financial information nor in the calculation of the target working capital.

- The buyer included a $10 million provision for excess inventory in the closing statement.

- The seller disputed the inclusion of the provision, as it was inconsistent with past practice.

The parties ended up in a prolonged resolution process arguing GAAP versus consistency.

4. Don’t underrate the estimates process

Typically the post-closing price adjustment process is intended to be a fair and equitable way to true-up the estimated purchase price based on the actual closing balance sheet, which cannot be determined until after legal closing. In the flurry of activity leading up to closing, which can be magnified in periods of uncertainty, the pre-closing estimates process can sometimes be overlooked, creating a number of problems. Consider the following:

- Institutional investors typically don’t want to overfund an acquisition on Day One. Nor do they wish to write a large check after closing.

- If the estimated purchase price is overstated but the buyer can recover value only up to the adjustment escrow amount, the post-closing price adjustment process may no longer be fair and equitable, and so review of the estimates is key.

- Publicly traded companies may want to manage market expectations, so they may be incentivized to avoid a negative post-closing price adjustment rather than disclosing a significant contingent liability or reduction in the purchase price.

- Carve-out transactions create additional complexity about the ability to prepare reasonable estimates, especially if the estimates are prepared before the carve-out has actually been fully implemented or if reimbursement of TSA services is commingled with pre-closing activity.

- Sellers may inadvertently create a precedent in preparing the estimate, to the extent a certain position is taken in the estimates that is contrary to the closing accounting principles set out in the agreement.

- Both parties should be aware of oversimplified estimates without a methodology that provides a reasonable basis for determining the estimated purchase price. After all, the sale and purchase agreement typically stipulates that these must be management good-faith estimates.

It is therefore important to understand the incentives of each party and the unique deal dynamics when preparing or reviewing the estimated purchase price. In all situations, timing is important – both to prepare the good-faith estimates and to have ample time to review the estimates (and provide comments or adjustments, if needed).

Case in point #4: No post-closing recovery, no buyer’s remorse

- The agreement capped the true-up between estimated and final purchase price at the adjustment escrow amount of $10 million.

- The buyer did not compel the seller to provide estimates with “reasonable supporting documentation” or contractually require the seller to consider the buyer’s comments on the estimates in good faith.

- Post-closing, the buyer found additional liabilities for indebtedness, uncollectible accounts receivable and obsolete inventory of over $30 million.

However, the buyer’s closing statement was limited to $10 million for any additional downward adjustments to the purchase price, and it missed out on approximately $20 million of value. The buyer’s closing statement position, as limited to the contract, was then subject to dispute by the seller, and good faith negotiations led to further erosion of deal value.

The bottom line

Value can be won or lost through the determination of the closing accounts price adjustments. Being prepared and strategic, having an integrated team of advisors and knowing how the contract supports your preferred pricing position should strengthen your negotiating position and result in a more favorable outcome.

PwC Director Andrea Mazur and PwC Director Ada Yi contributed to this article.