{{item.title}}

{{item.text}}

{{item.text}}

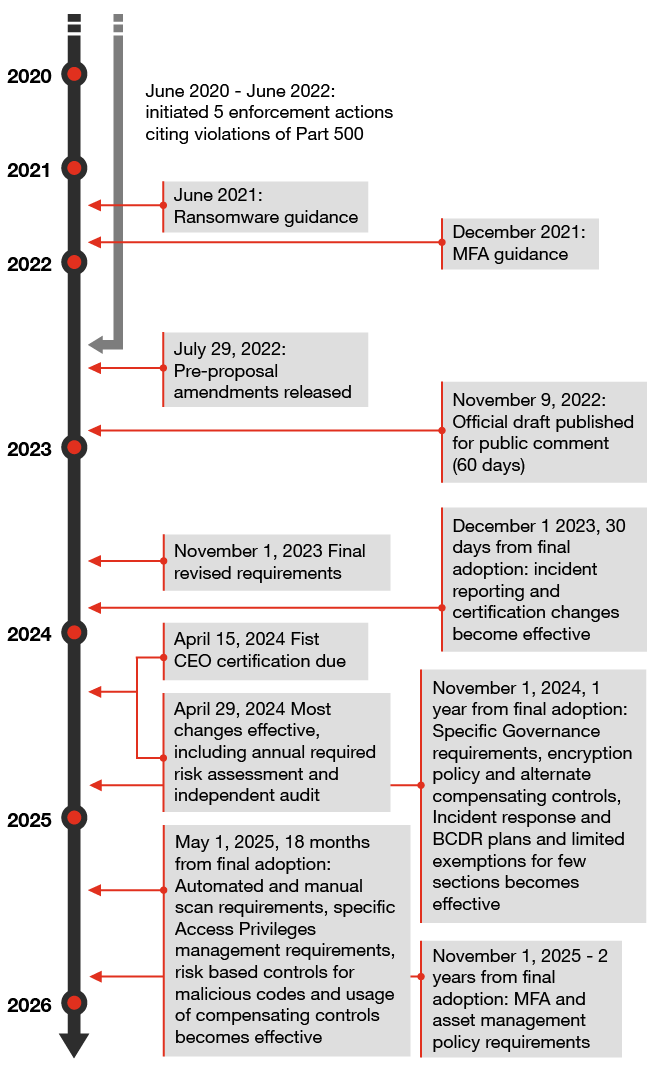

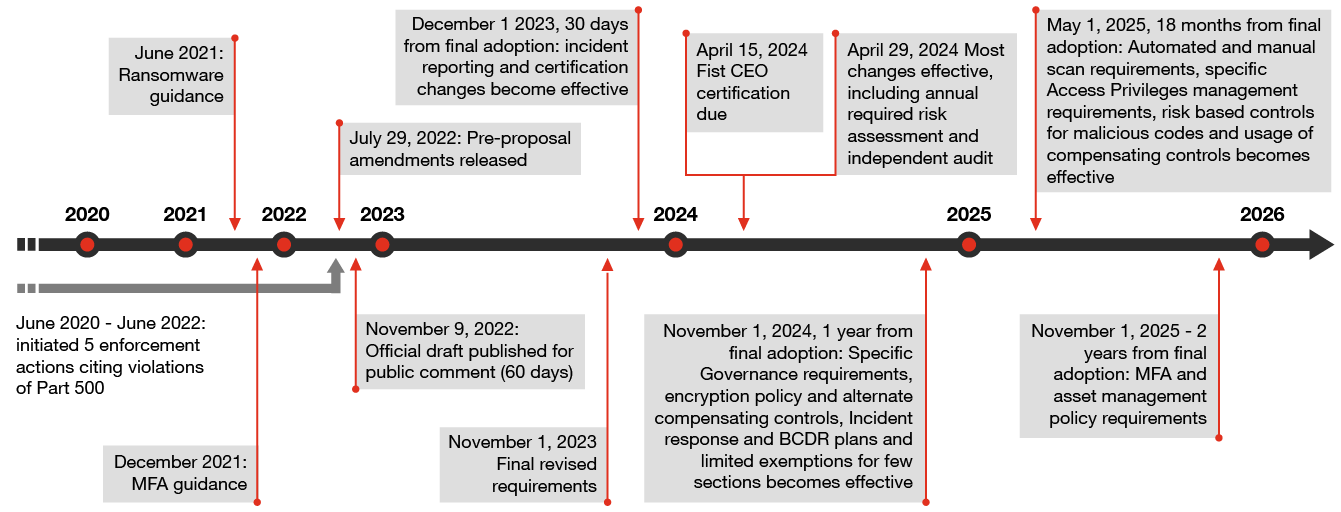

Revisions to the New York State Department of Financial Services (NYSDFS) Part 500 cybersecurity regulation are now final — just in time for 2024 budgets. First proposed in July 2022, the draft underwent several iterations since, notably in November 2022 and June 2023. While some of the more prescriptive elements of the proposed rule have given way to a more flexible, risk-based approach, most of the rule’s revisions remain intact. The final rule retains enhanced requirements for governance, risk assessments, password and data management, as well as the net-new requirements for asset inventory, business continuity and disaster recovery (BCDR), and independent audits.

With this revision, NYSDFS is emphasizing compliance and governance from several angles — from the top down, by requiring CEO and CISO signoff based on data and documentation and a required role for the board; from the bottom up, by setting minimum required frequency for control execution and requiring documentation; and from the side, by injecting the independent audit requirement as an independent check on the program.

As of December 1, 2023, not only must the highest ranking executive (usually, and hereafter, the CEO) now sign off on compliance with the regulation, but this certification must now be based on data and documentation sufficient to accurately determine and demonstrate material compliance (described further below), including any reliance on third parties and affiliates to meet the requirements. Because this change takes effect on December 1, 2023, it will be in place in time to lift the bar for this year’s certification, due for submission by April 15, 2024. Where some firms may have relied on control owner attestation, evidence of control execution would now be expected. If a firm can’t certify its material compliance, it must file a written statement and include timelines for remediation to obtain material compliance.

The final rule requires Class A companies (large companies, as defined further below, facing the most stringent requirements) to execute independent audits based on their risk assessment, rather than on an annual basis. While the annual requirement is no longer stated, the audit is now linked to the risk assessment, which the revision now requires to be refreshed at least annually.

Independent audit requirement starts April 29, 2024, for large companies. Class A companies must conduct an independent audit of their cybersecurity program meeting NYSDFS rule 500 requirements based on their risk assessment. In the discussion of public comments, the regulator acknowledged that many companies typically conduct multiple independent audits annually of their cybersecurity program capabilities (e.g., incident response, multi-factor authentication (MFA)) based on the risk level each year, and aligned this requirement with the regulation’s overall flexible, risk-based approach. We expect these audits to play two roles, therefore — meeting the new requirements but also informing and supporting the certification process, by supplying an independent, evidence-based view of the cyber program.

With the risk assessment now required at least annually, covered entities should use the assessment to inform their audit plan by focusing not only on traditional cybersecurity capabilities but also technology operations (such as net-new requirements for asset inventory) and operational resilience (such as net-new BCDR planning and testing).

The waiting is over. Now’s the time to take action.

Recent changes have elevated additional leading practices to mandatory status. Using these amendments as a guiding framework to enhance your cybersecurity initiatives can help not only to prepare for regulatory scrutiny but also to safeguard your clients, your organization and its reputation.

While required adoption of some changes can occur up to two years from November 1, 2023, organizations need to act now to enable alignment with the changes that must be adopted before year-end 2023.

{{item.text}}

{{item.text}}