Financing the Net Zero Transition

Making the transition to a net zero economy will only be possible with huge financial support and multilateral cooperation. The OECD estimates that we need to invest $6.9 trillion annually in low-carbon, climate-resilient infrastructure–just under $1,000 per year for every person on the planet–and by most estimates, this will only partly solve the problem.

The work is underway. In the Race to Zero initiative, launched in June 2020 by the United Nations to help to limit global warming to 1.5°C, nearly 1,700 companies have committed to halving emissions by 2030 and achieving net zero emissions by 2050. Those signed up include some of the world’s largest emitters.

Leading technology firms have pledged to eliminate emissions across their entire value chain by 2030, with some companies like Microsoft and Google committed to go beyond net-zero to become "carbon-negative", purchasing 24x7 renewable energy.

Elsewhere, oil and gas companies are setting net-zero targets to not only cover their Scope 1 and 2 emissions, but also their Scope 3 emissions from the use of their products. Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) currently tracks 34 oil majors globally, including Shell, BP and ConocoPhillips, that have set net-zero targets.

Meanwhile, utilities firms, including Duke, Dominion and Enel, have similarly set net-zero targets for their Scope 1 and 2 emissions.

3.5 billion metric tons

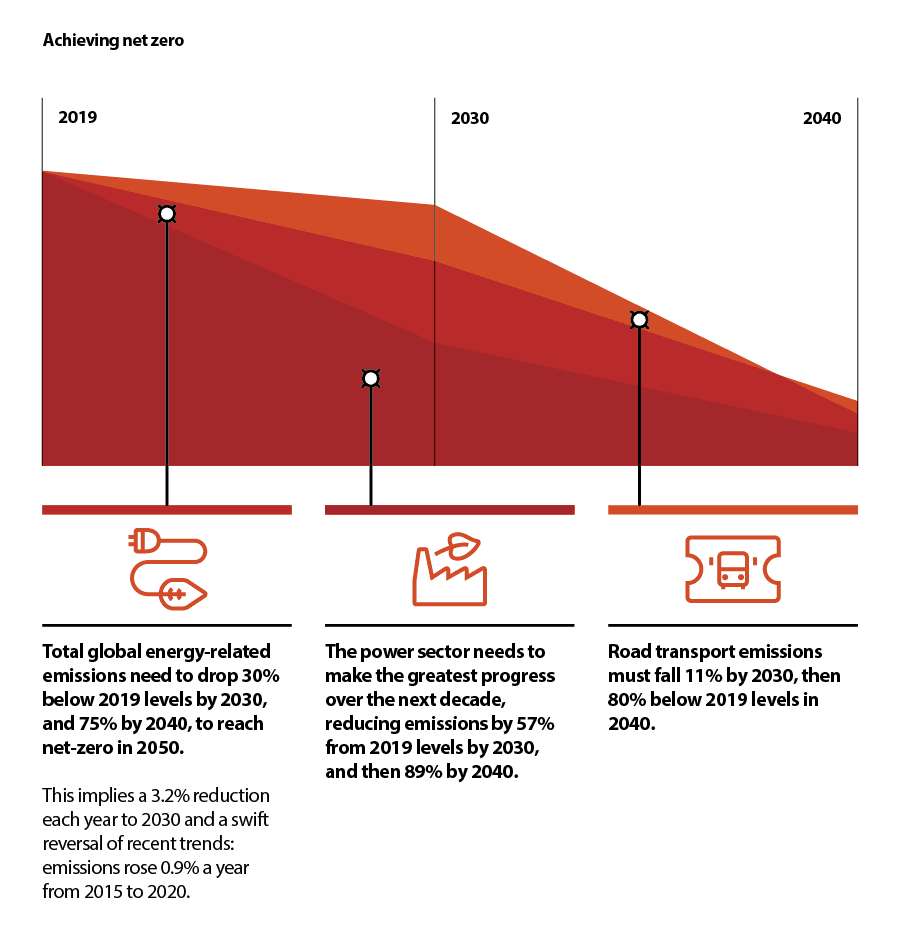

It’s clear that the simplicity of the “net zero” target has acted as a powerful rallying cry for climate action. But making it a reality is a far more complex process. And as recent energy price rises have demonstrated, a badly handled transition could contribute to a global energy crisis that sends shockwaves through both industries and entire economies. The need to act is urgent; mid-century is the common target date, but the work must start now.

“The world needs to halve emissions by 2030, but we are nowhere near being on track,” says Peter Gassmann, Global Strategy& Leader and Global ESG Leader, Partner, PwC Germany.

Source: BNEF

“Nations cannot meet their net zero targets without transforming their economies and the industries within them,” adds Gassmann. “There needs to be a complete systemic transformation, with the leaders in each sector collaborating with each other.”

While the role of business is just one piece in the puzzle, it’s an important one. Investors, regulators, customers and employees are increasingly demanding companies play their part to help spur multilateral cooperation in the transition to a cleaner economy.

The rise of ESG investing

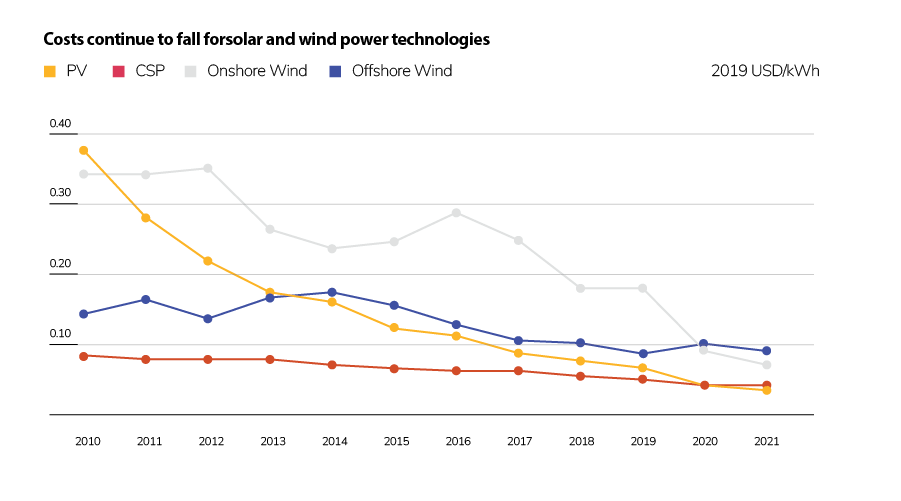

A common refrain used to be that making the shift to low-carbon products and services was too expensive, but in many sectors a tipping point has been reached. In 2021, many climate-friendly energy options are on parity, or cheaper, than their traditional high-carbon alternatives. As a result, simple financial logic is now helping to dictate the flow of investment.

The amount of money coming into the sector could be even larger with the right financial market infrastructure (FMI). PwC’s Sept. 2021 report, Scaling the sustainable finance market, concludes that a cross-border FMI-driven approach can increase the growth of the sustainable finance market by up to 2.5%, equivalent to an additional $25 trillion mobilized in the sustainable finance market by 2030 and up to 1.1 years saved in financing the UN SDGs.

The costs of clean energy technologies such as wind and solar power—along with battery storage—have tumbled in recent years, driven by improving technologies, economies of scale, increasingly competitive supply chains and growing developer experience.

Since 2010, utility-scale solar PV power has shown the sharpest cost decline at 82%, followed by concentrating solar power (CSP) at 47%, onshore wind at 39% and offshore wind at 29%, according to figures from the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).

Source: International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).

Capital is now flowing to low-carbon solutions, while many investors are increasingly viewing high-carbon investments as a higher risk.

“There is a €4 trillion gap in Europe between money that wants to be 1.5C-aligned and the reality of the companies they can lend to,” says Laurent Babikian, Joint Global Director, Capital Markets at CDP. “Only a tenth of listed companies in Europe are 1.5C-aligned, and Europe is leading the way on this.”

Many investors are looking to lower carbon options because they see high-carbon investments as a higher risk. In the future, companies with poor ESG performance will face an increased cost of capital and in some cases, will even struggle to access funding options. According to Gassmann, more and more investors are considering longer-term value creation path over short-term profit optimization.

“We’re already starting to see the cost of capital for 1.5C-aligned companies being lower than for others,” adds Babikian.

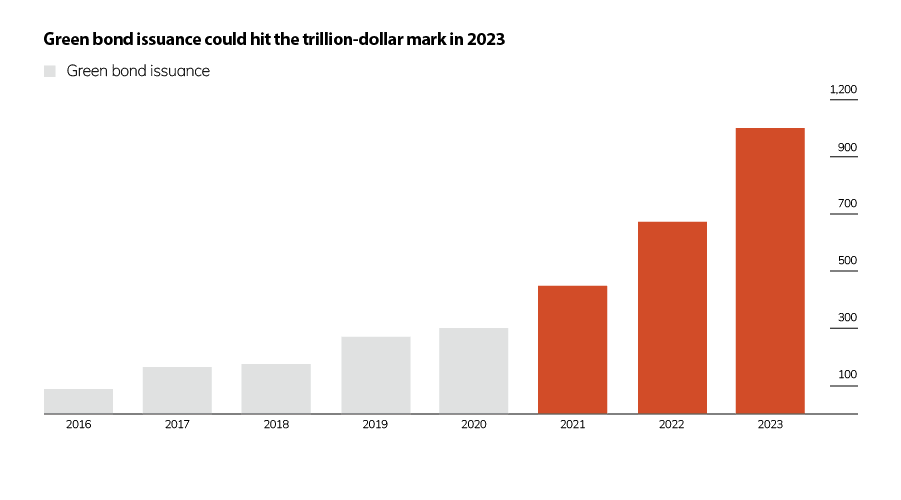

Green bonds, designated for specific climate and environment-related projects, have developed rapidly since the first green bond was issued by European Investment Bank (EIB) in 2007. While rising regulatory scrutiny has started to temper uptake in the second half of 2021, their growth has risen in step with the growing awareness and consciousness around climate change, as well as attempts to build a low-carbon future.

Source: Climate Bonds Initiative - Note: 2021, 2022 and 2023 figures are CBI forecasts

However, for capital to flow to assets aligned with net zero, companies and projects must be well-structured, have strong business cases and be transparent about their progress toward clearly stated sustainability targets. Because many green technologies are still in their infancy and many projects are new, investors are less comfortable with the risks involved. “Derisking carbon transition projects and companies will be key to ensuring that we can finance future obligations,” says Gassmann. Underscoring this imperative is recent PwC research indicating that most global investors demand returns on ESG initiatives that are similar to returns for conventional investments.

It is becoming clear that investors are obliging asset managers to look for low-carbon investments, resulting in more sustainable products being launched. Even private equity now needs an ESG strategy; it adds to the exit value. PwC research into responsible investment found that 72% of PE firms always screen target companies for ESG risks and opportunities at the pre-acquisition stage. And while the primary motivation for considering ESG issues used to be to help manage risks, now the main driver is value creation.

“This is creating a virtuous circle,” says the Rev. Kirsten Snow Spalding, Senior Program Director of the Ceres Investor Network. “Investors engage companies, make investments in climate solutions and engage with policy makers so that the market signals and public investments support the net zero commitments being made by companies and investors.”

Our moment

Collaboration is essential

The scale of the challenge—and the speed of change required—is so large and so complex that the availability of technologies and finance is not enough. A strategic, cohesive response is needed from all stakeholders—not just companies, but also investors, governments, banks and civil society.

“The longer we wait, the harder it will be,” adds Olwyn Alexander, Global Asset and Wealth Management Leader, PwC Ireland (Republic of). “Instances like the recent IPCC report are forcing leadership teams to look at ESG with a mix of anxiety and enthusiasm.”

Achieving this unprecedented collaboration requires external expertise to bring different stakeholders together to identify and bridge gaps, so that all work in harmony toward the common goal of net zero. However, “the different stakeholders don’t have all the information that they need,” warns Alexander.

“Lots of companies publish sustainability data, but it is fragmented, and the way it is collated and published is inconsistent. It makes assessing data particularly challenging.

“Consistency of data is one of the biggest challenges in creating the incentives needed to drive investment. We need a shift to consistent, independently assured and verified sustainability reporting,” she says. “It should be as robust as financial reporting, where standards are consistently applied around the world. Until there is consistency and verification we won’t have the trust that is needed in what companies are doing to tackle climate change.”

PwC global chairman Bob Moritz is among those who have called for global standards on non-financial reporting.

Setting new, consistent standards

The penny appears to have dropped and momentum is building towards convergence. Key standards setters SASB (Sustainability Accounting Standards Board) and IIRC (International Integrated Reporting Council) are merging to create the Value Reporting Foundation while the EU, U.K. and U.S. are creating stricter climate reporting requirements for companies. Indeed, there are so many initiatives that it can be hard to keep up with them all, and where they fit into the overall regulation landscape.

Independent consultants and integrators can play a key role in helping to create the standards, transparency and trust in the systems needed to enable governments, investors and businesses to agree on targets and what constitutes progress. They can also help combine the power of finance, incentives and taxes into single structured products, as well as create markets and platforms where emissions can be traded.

“The political, social, economic and financial equations at play are complex and multifaceted—involving capital, structured financial products, regulations, taxes, carbon markets, policy, standards and voluntary commitments,” Alexander points out. “There are legitimate concerns about ‘greenwashing,’ and how to balance the concerns of workers and customers who may be impacted by the transition against the imperative to decarbonize the entire economy.”

Shutting a highly polluting mine in South Africa, for example, would have positive environmental impacts, but very high social costs, she says. “You really have to look at the wider impact of everything you do to get it right. There must be a ‘just transition’ for those sectors, regions and communities that will be most affected.”

Spalding adds that “every company needs to consider both the impacts on the workforce and on the communities where they operate as they wind down carbon intensive operations and ramp up lower carbon alternatives.

New expectations for business

Investors have a crucial role to play in accelerating the transition by influencing the companies they invest in to change their business models and governance to bring down emissions, says Spalding. Increasingly, investors are joining forces in initiatives such as the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative and Climate Action 100+ to engage with companies more effectively, she adds.

“Net zero sets a new expectation on how a business should be run, both in terms of addressing external pressures and because it creates a recognition that sustainable businesses perform better in the long run,” Gassmann says.

While a number of companies are selling off their high-carbon assets to reduce their own carbon footprints, this does not solve the problem because the assets remain operational and carbon-emitting under a new owner. “This is why Ceres and Climate Action 100+ advocate investors engage with companies to make change instead of divest from these companies or assets,” points out Spalding. “We want to see change in the real economy – not just a change of ownership of polluting assets.”

New models to tackle this issue are emerging. In one example, the Asian Development Bank has teamed up with a number of investors to buy coal-fired power plants in the Philippines, Vietnam and Indonesia and shut them down over the next 15 years – much sooner than their projected end of life, but long enough to allow workers to retrain and find new jobs.

The transition to net zero is not just about mitigating climate change and avoiding risks such as reputational issues or stranded assets. It also presents a huge opportunity for businesses and investors to create and fund innovative technologies and business models, implement efficiencies and take advantage of incentives from governments looking to meet their own targets.

This article was produced by Bloomberg Media Studios and the original article can be found here.

For more information, please click here.

Contact us

Olwyn Alexander

Global Asset & Wealth Management Leader, Partner, PwC Ireland (Republic of)

Tel: +353 (0) 1 792 8719

Peter Gassmann

Global Leader of Strategy&, PwC's global strategy consulting business, Strategy&

Partner, Risk Assurance Services, PwC Canada Board Chair, ESG Practice and Net Zero Leader, PwC Canada

Tel: +1 604 806 7711