Oil output is cut but capacity expands

OPEC+’s most recent cuts came after it had recovered to baselines

In October, OPEC+ cut production for the first time since May 2020, signalling the start of a new oil market strategy which has significant implications for exporters in the Middle East (all except for Qatar are members) as well as importers.

The October cut followed a period in which the market had largely been driven by the post-pandemic recovery in demand, and by the geopolitics of the war in Ukraine. Throughout this period OPEC+ steadily tapered its production cuts, with pauses and slight monthly variations (and deeper Saudi voluntary cuts in early 2021), but the destination was clear. In August, the organisation’s production quota finally returned to the original baseline of 43.8m b/d, although actual production was only about 40.2m, given the serious production constraints that have developed for many of its members outside of the region.

The tapering was broadly in line with the plan agreed upon at the July 2021 OPEC+ meeting, although the organisation did quietly drop one clause that would have allocated higher baselines to the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iraq from May 2022. The clause had been inserted after the UAE pointed out that the original baselines, derived from October 2018 production levels, did not adequately reflect its increased capacity of about 4m b/d, and therefore meant that it was bearing a larger burden from the cuts than other OPEC+ members.

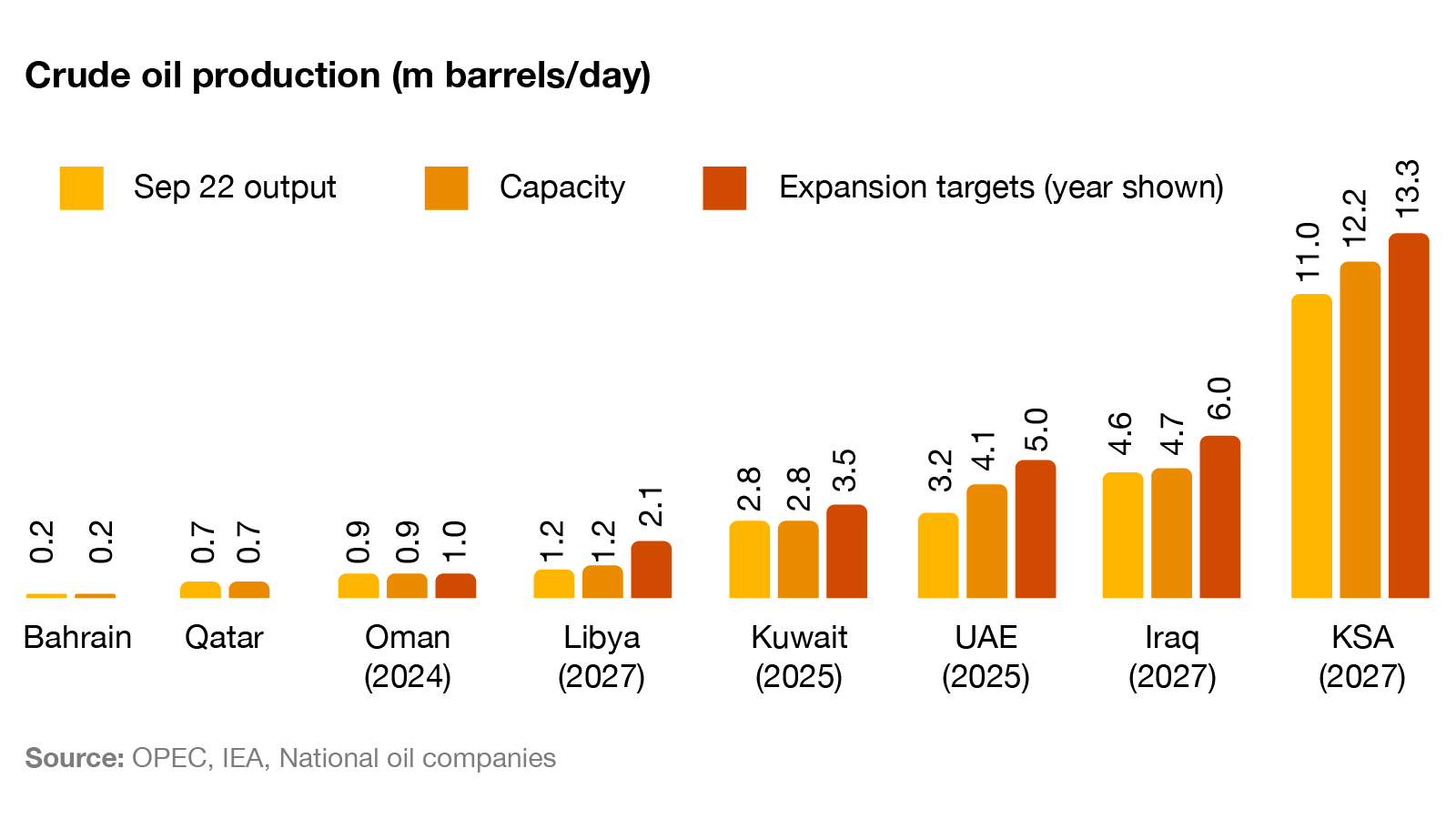

High prices this year reduced the impetus to adjust the baselines (oil was under $75 when they were negotiated back in July 2021). However, this just delays the difficult but necessary resetting of baselines. The UAE’s allocation is still 20% below its capacity, and Saudi Arabia’s is about 10% below, whereas most other members of OPEC+, including Kuwait, have allocations that are at or above their current capacities (see graph).

OPEC+ is extended to 2023 in readiness for a demand shock

The initial cut in quotas for October was only by 100k b/d, reversing a similar increase in September, which were the smallest ever monthly adjustments since OPEC+ quotas were introduced in January 2017. The biggest change comes into effect this month, with allocations reducing by 2m b/d, about 5%. The true cut is expected to only be about half that amount because few OPEC+ members outside of the GCC were producing above these new quota levels.

The GCC has been willing to bear this burden partly because the immediate boost to price should largely offset the reduced volume (and market moves bear this out) and also because the agreement extended the OPEC+ pact for a seventh year, which would have expired at the end of 2022. OPEC’s forecasts, as well as those of the IEA and others, still anticipate solid demand growth of over 2m b/d in 2023. However, there are concerns that the global economic slowdown could be even worse than the IMF’s latest baseline forecast of 2.7% GDP growth, and therefore maintaining the agreement leaves exporters with options in the event of a demand shock. 2022 may bring back memories of 2008 when the global financial crisis also ran ahead of expectations and drove down prices sharply over the winter, after having hit record levels only a few months earlier.

Expansion plans vary in scale and feasibility

Even as the GCC cuts production and contemplates another year of quotas, they continue to invest heavily in expanding their capacity. This strongly suggests that they do not expect OPEC+ controls to remain in place indefinitely and, while they remain in place, they could motivate a reassessment of burden sharing in 2023, for example through an adjustment of baselines.

The UAE is making the most progress on ambitious expansion plans. ADNOC had originally planned to boost its capacity from 4 to 5m b/d by 2030 but has been making rapid progress in key fields such as Upper Zakum, where it awarded $3.4bn in drilling contracts in August. Recent media reports suggest that the target data had been moved up five years to 2025. Moreover, a new target of 6m b/d is reportedly being contemplated for 2030—about half its current capacity and double its OPEC+ quota. Saudi Arabia plans to boost capacity by 1m b/d by 2027 - a 9% increase. There are more ambitious targets from other countries with Kuwait aiming at 3.5m (+25%) by 2025, Libya at 2.1m (+75%) by 2027 and Iraq at 6m (+28%) also by 2027 (and potentially up to 8m by 2028). These three countries all have the reserves required to support their planned expansions but have also frequently missed previous targets. For example, Libya’s 2.1m target was originally set for 2021 but has repeatedly slipped as conflict has hindered investment. This makes the possibility of expansions elsewhere more uncertain than for UAE and Saudi Arabia.

Oman does not have a formal national target, but PDO, which is responsible for 80% of its crude production, is aiming to lift its output to 0.7m b/d by 2024, from about 0.65m currently. Qatar is mainly focused on LNG expansion but aims to plateau its crude output at around 0.7m b/d, after a long period of steady decline. Finally, Bahrain doesn’t have specific published national targets and is currently focused on maintaining current output levels from its two conventional fields. The wildcard here is the Khaleej al-Bahrain shale oil reserves discovered in 2018, which, if developed, has the potential to increase Bahrain's capacity sharply - perhaps more than doubling it. Production was slated to start in 2023, but so far no announcements have been made.

Oil reserves can be monetised during the energy transition

It may seem strange that Middle Eastern oil exporters are so focused on growing capacity after producing well below their existing capacities for the last six years and at a time when they are taking the energy transition increasingly seriously, investing in renewables and hydrogen (see our July report) and announcing net-zero emissions targets.

The rationale is that even if global oil demand is nearing a peak and may begin to decline in the second half of the decade, the region is highly competitive on both production costs and the carbon intensity of emissions. Therefore as global demand declines there is scope for increased output from the region, building market share. Most states in the region have production-to-reserve ratios of many decades so it makes sense to monetise these during the energy transition. The revenues from oil production can then be reinvested in renewables, which also means they can reduce domestic consumption of hydrocarbons and export a larger share of production. This is likely to make it increasingly difficult for OPEC+ to maintain a consensus into 2023, as producers in our region seek a way to maintain tools to manage the global oil balance while creating space to increase their output in line with their current and future capacities.

Contact us

Richard Boxshall

Global Economics Leader and Middle East Chief Economist, PwC Middle East

Tel: +971 (0)4 304 3100