Credit ratings strengthen amidst oil boom

Ratings begin improving after years of decline

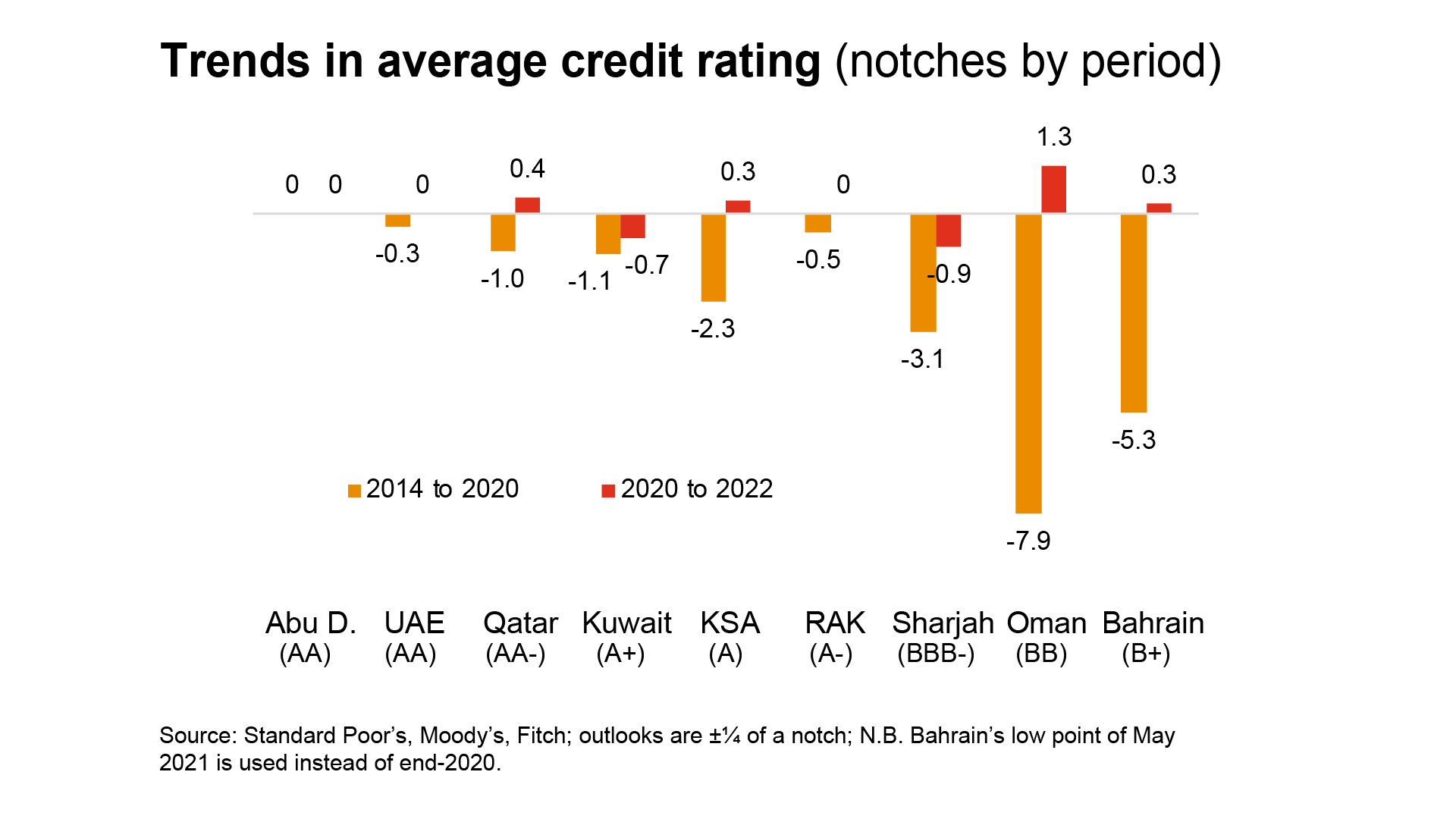

Strong oil prices combined with relatively restrained fiscal policy brought the GCC back into an aggregate fiscal surplus in 2022 for the first time since 2014, along with surpluses for most states individually. This has resulted in a series of positive actions by credit rating agencies, reversing a long period of decline in the aftermath of the previous oil boom that left several states struggling for years to bring bloated budgets under control, before facing an additional fiscal shock from COVID-19. However, that difficult period resulted in policy changes and stronger controls that have supported recent rating improvements and should make it easier for Gulf states to manage through future periods of weak oil revenues.

The biggest improvement has been for Oman, which previously suffered the region’s biggest rating decline, dropping by eight notches between 2014 to 2020. The turnaround under Sultan Haitham began with a five-year fiscal plan announced in late 2020. Reforms included spending controls, the introduction of VAT, then reinvesting the 2022 windfall to reduce the stock of public debt by 15%. This all led to upgrades in 2022 from Fitch and Moody’s and two consecutive upgrades from Standard & Poor’s. Qatar also received an upgrade from Standard & Poor’s, reversing its first-ever downgrade in 2017, and a positive rating outlook from Moody’s. Negative outlooks for Saudi Arabia and Bahrain were removed in 2021 and Standard & Poor’s now has positive outlooks on both, with Fitch also positive on Saudi Arabia, indicating the possibility of upgrades this year if fiscal improvements continue.

There are two exceptions to the positive trends. Kuwait suffered downgrades in 2021, even as oil prices rose and its fiscal balance improved, because of governance challenges. Its ratings did at least stabilise in 2022 and could see improvement in 2023 if the new National Assembly and government, formed in November, continue to cooperate more effectively and pass a reasonable budget. The emirate of Sharjah suffered further negative actions in 2021-2, most recently a downgrade by Moody’s in July, as it struggled to control a structural deficit and received little benefit from oil prices as it produces few hydrocarbons.

Public finances return to surplus

The GCC recorded a deficit of -10% of GDP in 2020, the weakest since the low oil prices of the early 1990s and the seventh consecutive year of aggregate regional deficit. The recovery was rapid, however; the deficit narrowed sharply to just -1% of GDP in 2021 and in 2022 returned to a surplus of about 3% of GDP (based on preliminary results from Saudi Arabia and Oman and estimates for the others). Bahrain may have eked out a tiny central government surplus, which would be its first since 2008 and two years ahead of target in its 2021 fiscal balance plan, although consistent off-budget expenditure means that there is likely to be a deficit at the general government level. Other Gulf states tend to have stronger balances at the general level, which includes off-budget income from sovereign wealth funds.

Spending restraint largely persists

Oil exporters always face the temptation of stalling or reversing fiscal reforms and ramping up expenditure during times of high or rising oil prices. During 2003-14, regional expenditure increased five-fold, an average of 15% a year with a peak of twice that in 2008. However, in the latest cycle things have been much more moderate to date. There was about a -2% y/y decline in 2021, even as oil revenue increased by about a half. In 2022, the IMF expected only about a 6% increase in expenditure even as revenue increased by a third. So far only Saudi Arabia and Oman have reported their preliminary outturns, showing higher than forecast spending growth of 9%, partly a consequence of fuel subsidies.

However, it is encouraging that governments are showing restraint in core inelastic areas of spending, which are harder to row back. For example, salaries in Saudi Arabia only increased by 2%, returning to 2019 levels, and Oman’s core current expenditure (excluding subsidies and gas purchases) only rose by 2%.

Part-year results from other Gulf states also show some signs of restraint. Consolidated UAE expenditure was only up by 4% y/y in the first nine months and salaries only by 1%, despite a 36% increase in revenue. Qatar’s spending was up by 13% over this period, but the World Cup was a one-off driver. Bahrain has only released outturn data for H1, actually showing a -1.5% decline in spending.

This spending restraint is particularly significant during a period of high inflation. Although inflation in the GCC is lower than in many places globally (as noted), a 4% increase in prices in 2022 is still as much as in the previous five years combined.

New taxes planned for 2023

From the budgets published to date, another positive sign fiscally is that there have been no reversals in tax policy and even some significant new measures, which is unprecedented during an oil boom. Saudi Arabia maintained the 15% VAT rate, despite the Crown Prince indicating in 2021 that it would be reduced at some point, and Bahrain doubling its own rate to 10%. The UAE law to apply a 9% corporate taxation was issued in December, which comes into force in June this year, and Oman’s parliament has begun debating a draft law for personal income tax - a first in the region.

2023 budgets also indicate plans for continued restraint. Saudi Arabia’s budget plans a -2% cut in expenditure relative to its preliminary 2022 outturn and Oman’s budgets a similar cut on an underlying basis (excluding fuel subsidies, gas payments and allocations for future debt obligations). Meanwhile, Qatar is budgeting a -3% cut compared with its 2022 budget. The picture in the UAE is more mixed with Dubai planning a 13% spending increase, the federal government a 7% hike and Sharjah a -6% cut, all relative to their 2022 budgets.

Contact us

Richard Boxshall

Global Economics Leader and Middle East Chief Economist, PwC Middle East

Tel: +971 (0)4 304 3100