Our first Middle East State of Climate Tech report finds that by combining its nature-given advantages with focused research and funding, the region can pioneer the development of technologies that help achieve global climate goals

The dangers of unchecked climate change are very real for the Middle East region, where arid landscapes and low water levels are especially vulnerable. The threat of multi-year drought, frequent sandstorms, and rapidly rising temperatures – expected to increase by 5 degrees Celsius by the year 2100 – puts the region’s 400 million people at growing risk.1

Many of the region’s governments have set out clear net zero ambitions for the coming decades but this is set against a wider global picture of record rising greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions rates and the recent COP27 summit in Egypt highlighting few signs of progress toward accelerating action to tackle the climate crisis. Furthermore, both globally and regionally, the pace of investment in the very technologies that could produce new climate solutions has slowed.

In this context, the Middle East has a unique opportunity to not only take action but, potentially, to lead. By mobilising a large-scale, collective investment response, the region can play a leading role in developing innovative solutions that significantly add to the battle to halt climate change. Later in this report, we take a look at five such technologies that our analysis suggests have high potential for growth and impact — solar energy, bioreactors that convert energy into edible protein, green hydrogen and synthetic fuels, recycled plastics, and waste-to-energy — but others are also within reach, including sustainable water desalination, carbon capture, and nature based solutions for arid environments.

In making a priority of such technologies, Middle East countries could reorient their own economies to become greener, and proactively address some of the major climate challenges they themselves face, including water scarcity and drought.2

The region, and in particular, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, are well placed to pioneer climate technologies for several reasons. First, with pockets of high-velocity wind resources and the highest solar voltaic output in the world – which is also seasonally aligned with demand – the cost of producing solar, wind and green hydrogen in the Gulf is about one-third of the global average.3 Second, at a time when the global economy is in a phase of slowing growth, sovereign wealth funds are in a position to fund a major push into climate tech innovation in the region and beyond. And third, placing a pronounced emphasis on a greener Middle East and a global leadership in new climate-related technologies can accelerate already established goals to diversify the regional economy and build new sources of future prosperity.

Assuming a leadership role in climate tech will require focus, increased funding, and changes in regulatory and reporting requirements to enable the growth of a climate tech ecosystem. Broadly speaking, GCC and other countries in the region will need to address a range of localisation challenges as they seek to realise the vision of a green Middle East. If they manage to do so, the upside for the region—and the planet—is immense. At the same time, Middle Eastern countries have no choice but to take the lead in some areas in order to help themselves: the water-related challenges in the region, among other region-specific climate risks, demand that these countries find their own longer-term solutions.

Our latest Global State of Climate Tech analysis shows that climate tech4 in all its forms has grown strongly in recent years, as venture funds have focused on a range of promising technologies - primarily solar and wind energy - but also other nascent technologies, including green hydrogen.

At the global level, however, 2022 suggests some inertia in the growth of funding, with the bumper investment year in 2021 having given way to a cyclical decline in headline investment levels. Venture funding for climate tech start-ups fell to US$52 billion over the first three quarters of 2022, or 30% less than the same period last year (Exhibit 1).5 Moreover, the volume of critical early-stage funding required to scale up the next wave of climate tech success stories is trending in the wrong direction.

The downturn in climate tech investment globally stands in sharp contrast to the urgent calls at the COP27 summit and elsewhere for more - and more immediate – action to counter rising Earth temperatures. More positively, however, investment in climate tech globally still remains above the levels of two years ago, and the slowdown in this investment — which now represents more than one-quarter of every venture dollar invested – was less pronounced than the slowdown in the broader market for venture capital.6

After years of rapid growth, overall tech funding in the Middle East & North Africa has slowed

In the Middle East, broader tech investment trends largely track the global trend: after sharp increases in overall tech funding over the past few years that continued into the first half of 2022, the investment momentum has slowed in the second half of the year (Exhibit 2).

But these overall tech figures do not tell the full story about the growth in interest in climate tech in the region. Climate tech investment has continued to make substantial inroads as the green investment appetite grows and we identified 98 climate tech start-ups in the region that are currently receiving funding.7

Investment in Middle East climate tech gains momentum

Comprehensive and accurate data is hard to come by. But based on our analysis of the 12 Middle East countries we cover in this report, US$6 billion has been invested in climate tech since 2013 — and US$1.6 billion of that was invested in the first half of 2022 alone (Exhibit 3).

This momentum looks set to pick up further. Just days before the start of COP27, Saudi Aramco announced a US$1.5 billion sustainability fund, which will invest in technology needed to support the green energy transition.8 The fund will be one of the world’s largest sustainability-focused venture capital funds. The week before COP27 also saw the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the United States sign a US$100 billion strategic agreement in clean energy projects, focusing on investing in responsible and resilient supply chains, as well as promoting investment in green mining - an important announcement as the country gears up to host COP28 in 2023. Other substantial announcements in the region included UAE-based bank Mashreq, which plans to increase its sustainable financing to US$30 billion by 2030, as well as the Arab Coordination Group - an alliance of regional development funds - which, along with the OPEC Fund for International Development that coordinates climate finance, pledged to provide at least US$24 billion in climate finance by 2030.9

Sovereign wealth funds are increasingly playing a role in developing the greener profile of the region. This includes building out the necessary infrastructure and enabling the ecosystem needed for a greener economy. For example, Saudi Arabia Public Investment Firms (PIF and Saudi Tadawul Group), the holding company operating the local stock exchange, have introduced the Regional Voluntary Carbon Market Company that will help Middle East-based firms in their mission to offset their carbon footprint.10 This new company will trade verified, approved, and high-quality carbon equivalent credits certificates. PIF also launched Ceer this year, the first Saudi automotive brand to produce electric vehicles in the Kingdom, in efforts to reduce carbon emissions and support the region’s green agenda.

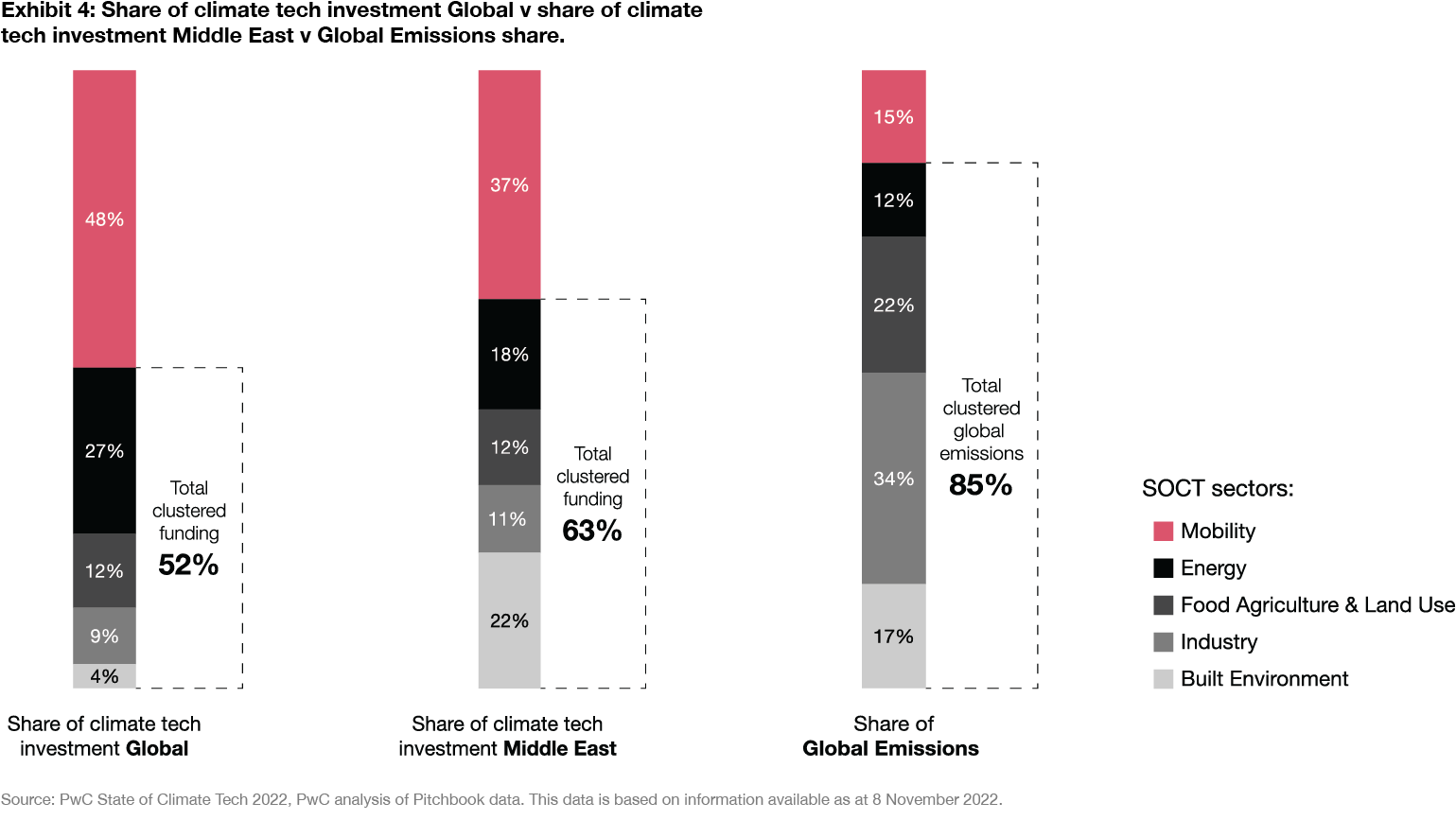

A further positive to highlight is the fact that the flow of climate tech investments in the Middle East is generally heading into the development of technologies where the most focus on greenhouse-gas emissions is needed: tackling sectors more heavily responsible for GHG emissions. Our data shows that almost two-thirds of investment is going into sectors that generate 85% of GHG emissions (Exhibit 4).

The story is not so balanced at a global level where, for example, about half of climate tech investment flows into the mobility sector, a disproportionate amount given that mobility generates just 15% of emissions. This leaves heavy GHG emitting sectors such as food, agriculture, land use and industry - responsible for 56% of GHGs - receiving only 20% of global funding.

Certainly, much more can still be done everywhere. Only about 3% of start-ups and other innovative companies in the region are engaged in climate tech, according to our Global State of Climate Tech report, based on an analysis of Pitchbook data. While renewables are being built out, they still only account for a modest proportion of energy generation in the region. For example, the share of clean energy in Dubai is just under 13% of the total installed capacity and expected to reach 14% by the end of 2022.11 The UAE goal is for clean energy to reach 44% of the total installed capacity by 2050, up from an average of about 7% today.12 Saudi Arabia, like the UAE, has relied heavily on oil for its energy needs and it has ramped up investments in solar power and announced its ambitions to generate 50% of its electricity from renewable resources by 2030.13

At a global level, the current market conditions, affected by the ongoing geopolitical tensions and other supply issues, may act as an accelerator of change, with the International Energy Agency saying that the current crisis could speed the transition to clean energy. Investment in renewable energy needs to double to more than US$4 trillion by the end of the decade to meet net-zero emissions targets by 2050, according to the agency’s recent World Energy Outlook.14 And climate tech markets have shown encouraging resilience: eight in 10 investors surveyed plan to increase their investment in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) products over the next two years.

We believe the Middle East is uniquely placed to take on a global leadership role in climate technology

The Middle East has a competitive advantage in a range of climate tech fields which, with focused investment, could mean the region is able to assume global leadership across these.

Here we look at five opportunities:

Until a few years ago, GCC countries were behind other emerging and developed nations in investing in renewable energies, but they are now catching up at speed. The International Renewable Energy Agency, in a 2019 report, noted that renewable energy had made “striking gains” in GCC countries, growing from niche technologies with little application beyond small-scale pilot projects to a pipeline with almost 7 gigawatts of new power generation capacity.15 Both the UAE and Saudi Arabia have made solar energy cost competitive as a result, and renewables have become an important regional investment focus.

Precision fermentation can convert renewable energy together with nitrogen, carbon, oxygen and organisms into proteins and other food substitutes. The technological challenge here is focused largely on bioreactors, which is where the energy-to-food process occurs. Bioreactors provide the uniform environment for the energy intensive chemical reaction, but for now are very expensive.16 If they can crack the technology and bring down the costs, GCC countries are well placed to become global leaders in this area — strong competitors in a market for global alternative proteins, which Credit Suisse estimates could be worth US$1.4 trillion by 2050.17 Their competitive edge for now comes from being low-cost renewable energy producers. In becoming global champions in this area, Middle Eastern countries would reduce their own food imports, which currently fill 85% of GCC domestic food needs.

Green hydrogen could become a major and versatile power source of the decarbonised future. Green hydrogen is made by using clean electricity from surplus renewable energy sources, such as solar or wind power, to electrolyse water. Electrolysers use an electrochemical reaction to split water into its components of hydrogen and oxygen. This produces no GHG emissions, but the process, for now, is expensive, and the technology can be improved. Building a robust supply of hydrogen could enable the decarbonisation of downstream industries, such as aviation with hydrogen-propelled short flights fuelled by hydrogen, as well as boosting the manufacture of materials such as green steel and green ammonia.

The GCC holds significant advantages in the production of green hydrogen because of its low-cost solar access, its coastline and access to water, space at low cost, and significant expertise in developing complex gas projects.

The Green Hydrogen project, implemented by the Dubai Electricity and Water Authority (DEWA), in collaboration with Expo 2020 Dubai and Siemens Energy, at the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park, is the first of its kind in the Middle East and North Africa to produce hydrogen using solar power.18And, Saudi Arabia is currently building a US$5 billion green hydrogen plant that will be the world’s largest, with production starting in 2026.19

Plastics have assumed a growing role in the global debate on sustainability. Demand for recycled plastic is soaring: more than 500 organisations representing 20% of the global plastic packaging market have committed to reducing virgin plastic use.20 Faced with this growth in demand, supply is failing to rise to the challenge — for now.

This demand and supply mismatch for circular plastics provides an opportunity for GCC players to go a step further, by developing a dual feedstock advantage. In other words, leveraging the continued access to advantageous feedstock for virgin plastic production and, at the same time, increasing access to quality plastic waste for recycled plastic production.21 Chemical companies, working in partnership with governments, would need to invest heavily to build world-scale recycling infrastructure over the next two decades, using the latest technologies and exploring opportunities to drive synergies with existing infrastructure.

Waste to energy uses non-hazardous waste that usually ends up in landfills and combusts it, generating steam for electricity production. The gasses are collected and filtered to reduce environmental impact and the ash is processed to recover metal for recycling. The positive effect on the environment from this technology consists of what is avoided: by reducing the volume of waste in landfills, the technology reduces the amount of methane emitted into the atmosphere. The Middle East is well placed to become a global leader in this technology, since good renewable energy resources in the region allow for hybrid plants, coupled with solar energy, meaning large cities in the region can ensure economy-of-scale waste to energy plants.

Sharjah opened the first such plant in the Middle East in May 2022.22 The project will contribute to avoiding the emission of up to 450,000 tons of carbon dioxide annually, with the plant producing 30 megawatts of low-carbon electricity - enough to supply electricity to about 28,000 homes in the UAE - and provide 45 million cubic meters of natural gas each year.

Localising today for an inclusive and green Middle East

To become key players in climate tech, Middle East countries will need not just to invest in others’ research but to pioneer technologies locally, like cost-effective electrolysers, bioreactors, air-capture, and many other promising technologies that can help mitigate climate change. This amounts to a localisation challenge, one that will also focus on the “S” in ESG – that is the social aspect of contributing to employment growth and economic development. Several countries and companies in the region are putting in place programs that seek to boost local content, including by better measuring of local metrics such as jobs created, improved local procurement, and fostering a stronger local ecosystem with small and medium-sized enterprises. Local content is now at the heart of many GCC government agendas, with national oil companies currently leading the charge in developing such programs, including Saudi Aramco’s In-Kingdom Total Value Add, ADNOC’s In-Country Value, Qatar Energy’s Tawteen, and SABIC’s Nusaned.23

While funding climate tech in the Middle East region is one part of the equation — arguably, the easy one - success requires a holistic and mission-oriented approach that hinges on the following seven key actions:

- 1. Connecting the dots & uniting investment efforts

- 2. Setting up a dedicated climate-tech fund

- 3. Reducing risk through longitudinal collaborations

- 4. Making climate tech a major R&D priority

- 5. Pivoting existing technical capabilities & expertise

- 6. Creating an enabling ecosystem for regulation

- 7. Galvanising young people into action

1. Connecting the dots & uniting investment efforts

The flurry of investment announcements before, during and after COP27 highlight the readiness of GCC players to play a role. But the stakes required in climate tech to make a genuine impact are so large that it makes sense to coordinate and potentially unite efforts. That means coordinating efforts among sovereign wealth funds, government programs, and national champion plans — essentially launching a climate-tech mission. Connecting the dots also goes beyond the region, to include deeper partnerships with countries that share common goals.

2. Setting up a dedicated climate-tech fund

Launching a dedicated climate-tech fund would send one clear signal of heightened coordination. Such a fund could leverage far more financing than disparate individual efforts, and make a significant difference at a global level. It would ideally be multilateral with allies and friends who share the same priorities across the region. In Abu Dhabi, for example, Global Mission, a nonprofit, has set up a US$17 billion fund aimed at progress in UN Sustainable Development Goals—far broader than just climate issues.24

3. Reducing risk through longitudinal collaborations

It will be important to create markets for local innovations. For example, producers of low-carbon synthetic fuels could connect with airlines or shipping companies. Companies looking to “green” their supply chains could also benefit from connecting with innovators.

For instance, advanced drone makers could work with pharmacies or drug companies to make fast and low-emissions deliveries of goods including vaccines and other medications that avoid conventional transport routes.

4. Making climate tech a major R&D priority

This would galvanise both local and global research and innovation communities. A recent initiative by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, for example, is expected to spur innovation around health and wellness, sustainable environment and energy, while adding roughly US$16 billion to the Kingdom’s GDP by 2040.25 Some climate technologies may take years to develop to the point where they are cost effective. That means they require long-term and “patient” funding that GCC countries could muster. Academic institutes and educational programs related to climate technologies, such as nature-based engineering and the hydrogen economy, could be singled out for priority treatment.

5. Pivoting existing technical capabilities & expertise

GCC countries could leverage their expertise as global leaders in oil and gas to develop other, capital-intensive, and geological complex green energies, including geothermal energy and carbon air capture and sequestration. The region’s capabilities and knowhow in petrochemicals could likewise be critical to develop synthetic fuel production and the hydrogen economy. Ammonia subsidiaries or business units can become core growth platforms.

6. Creating an enabling ecosystem for regulation

A strong ecosystem of enabling regulation and actions will be needed for climate tech initiatives to flourish. Many of the new technologies including carbon capture and storage are complex and come with potential geological and other risks of their own.26

Establishing regulatory sandboxes in which new approaches could be tried and tested in a careful but encouraging environment will help with their development. Better data about climate investments, including reporting requirements for companies, could already help track how and where funds are flowing, and thereby help set clear priorities.

7. Galvanising young people into action

Climate change is an intergenerational problem, and the Middle East, with its young populations, has the potential to galvanise its younger generation into action, providing new purpose and new vision for the region. This will require a focus on education, to ensure that climate science and its ramifications become part of the core curriculum. The first-ever youth climate forum held at COP27 this year was a good initial step.27

Seizing the chance to lead in climate tech

Beyond the existential questions that climate change poses, governments, companies, and individuals need to look at the opportunities that being on the forefront of green technology presents.

Reorienting local economies to become greener and developing the critical capabilities to help the world address climate change will have not just economic benefits but can position the region as a new global green hub.

It’s clear that although the upside - for the entire planet - of the Middle East taking a leading role here is immeasurable and that the investment required will be considerable, the stakes could not be higher.

Further delay is not an option.

Are you a climate tech innovator?

Nominate yourself for our Middle East Net Zero Future50 initiative. Learn more

Contact us